CSUMB Magazine

Statistics, Sidewalks & Social Justice

By Liz MacDonald

Published Feb. 2, 2019

While sidewalks may seem straightforward at first glance, they are actually an important and challenging aspect of city infrastructure management. It’s easier to create a new sidewalk than to repair or maintain an old one. In the city of Salinas, some sidewalks have waited 14 years for needed repairs to be prioritized in the city budget.

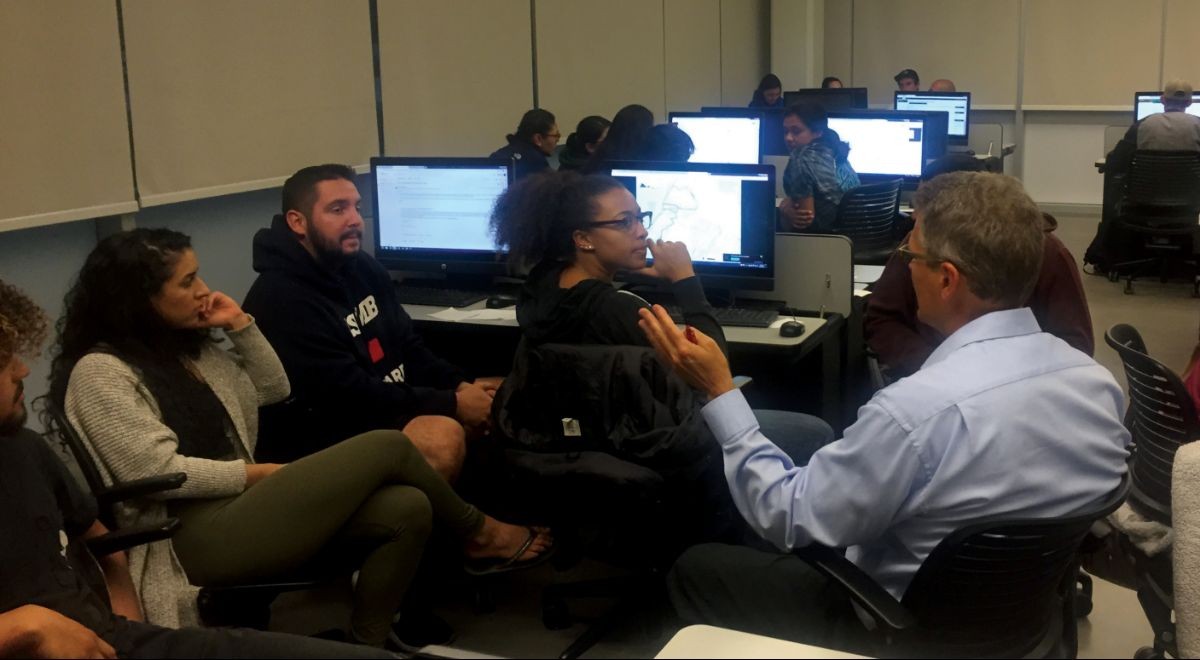

CSUMB students in professor Steven Kim’s statistics class spent a semester studying the conditions of sidewalks in Salinas at the request of city employees Steve Flores and Eric Sandoval. The students’ work helped them prioritize where sidewalk improvement funds should go to ensure that public services were being provided equally to all citizens.

Sidewalk conditions can predict whether a road is designed with cars or pedestrians in mind, and have an impact on a community's carbon footprint as well as its overall health. The Washington Post has reported on studies that linked poor sidewalk conditions to increased rates of childhood obesity and higher numbers of pedestrian deaths. Sidewalk conditions can also be an important indicator of inequality — especially when sidewalk conditions are mapped against community demographic data.

Being able to experience city government really left an impact on me and gave me a great set of skills I can use for the rest of my life.— Robert Banales

“Based on the data and statistical model, students concluded that the sidewalk condition was poorer in low-income areas when compared to high-income areas,” Kim said. As a result of the students’ work, the city decided to first focus on sidewalk maintenance in lower-income areas.

“As a statistics educator, I was very happy to provide hands-on projects to my students, and the empirical evidence helped the city to make a right decision.”

That’s just one example of the collaboration happening between CSUMB classes and city officials as part of the innovative Sustainable City Year Program (SCYP).

A Lean but Effective Machine

Now in its fourth year, the program is picking up momentum under its director, School of Natural Sciences professor Dan Fernandez. Last fall it received a best-practice award for university-community partnerships from the California Higher Education Sustainability Conference, beating out two other universities with similar programs.

“We are the smallest of the three and have a tenth of the budget. We run a lean but effective machine, which makes our model more realizable for cities that don’t have a budget,” Fernandez said.

The program works this way: Every two years, Fernandez requests proposals from area city officials for possible projects they would like help with from university students. The proposals include how much time city staff can devote to projects, and how much funding they can provide.

Fernandez selects proposals and begins “matchmaking” or pairing existing classes and faculty with needs the city has identified. The university and city work together for four semesters worth of projects. After two years, the program ends in one city and moves on to share the wealth of resources with the next municipality in the region.

“It’s a big shot in the arm for the city,” says Fernandez.

“The cities obtain near professional level analyses and products that they are either not able to afford or lack the internal expertise to do themselves,” says environmental science professor Rikk Kvitek. His class was matched to a project analyzing sewer spills and overflows for the city of Seaside.

The two-year timeframe works well, because the city gets an intense dose of research and creativity from the students in the short term, and then has time to assimilate the findings and ideas over the long run.

“Cities operate on different timescales than universities and students. Students are involved for one semester, but it may take a city years for the work to materialize,” Fernandez said.

It’s a model that began at the University of Oregon and has been replicated at more than 30 institutions across the country by a group called the Educational Partnerships for Innovation in Communities Network (EPIC-N). It’s a perfect fit for CSUMB, where real-world learning has been a core value since the university’s founding.

Many of the legal and logistical challenges of bringing students into the community have already been worked out through the university’s Service Learning program, which requires students to complete two community service projects to earn their degree. And while some SCYP courses may overlap with Service Learning, most are focused on completing a project within the classroom and don’t count toward the in-the-field Service Learning requirements.

So far about 25 wide-ranging CSUMB courses have participated in the program during its first two years in Salinas, and now in its second partnership with Seaside. Fernandez has matched courses in business, environmental studies, statistics, journalism, psychology, global studies and liberal studies. Most other EPIC-N universities have a full-time employee to coordinate the program, but Fernandez just “juggles it into what I’m already doing, which keeps our budget way lower.” It’s clearly a passion project for him; one which the university, the students, and the cities have embraced.

Opening a Door You Didn't See

Austin Fontanilla took Fernandez’s sustainability systems course during his last semester as an undergraduate. He took it because it sounded interesting, and he’d heard good things about the professor. Little did he know, the experiences he gained in the class would launch his career.

“Half of the semester was devoted to our final project: a transportation study for CSUMB and for the East Alisal Street corridor in Salinas. This project exposed me to the world of transportation planning. Before that I had no idea that people were paid to study traffic and write reports to government organizations,” Fontanilla said.

At the end of the semester, all the students in the class were forwarded a notice of an eight-month internship in transportation planning with the Transportation Agency for Monterey County (TAMC). Fontanilla got the job, and built on his experience with an AmeriCorp fellowship working in stormwater compliance for Salinas.

“If it weren’t for the class, I don’t know if I would be employed full time right now,” he says. “I had a great experience with it, but it was really challenging at times. If you put in the work, you might open up a door you didn't see was there.”

Current student Fady Ellaham is working on his capstone project through SCYP, a project to promote nature-rich, non-motorized transportation routes on Fremont Street. “For me, it provides experience for the things I want to do in my future,” he said.

Jessie Doyle is another student who’s leveraged her involvement with the program into a position with Seaside. She manages geographic information system (GIS) data as a member of the engineering department. She’s also a graduate student in environmental science and a teaching assistant, and she’s brought SCYP projects into her courses. Her students have mapped Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) ramps and helped geocode fire department data.

“This is an amazing program that connects students to real-world projects. My students learn skills that I didn't learn until after I received my bachelor’s (degree), which will only help them in their future job hunt,” Doyle said. In addition, Doyle gained public speaking experience through the program when she presented GIS work to the Seaside City Council.

Inner-workings of a City

Attending city council meetings is an important channel for students involved in SCYP to communicate their ideas and work back to Seaside. In the fall semester, Fernandez’s class time happened to overlap with city council meetings, and so his 22 students regularly attended and presented their work to the council.

“Students have this neutrality,” Fernandez said. “They can suggest innovative solutions that would be politically impossible for city staff to suggest.”

Business professor Dante Di Gregorio agrees. Students in his entrepreneurship classes have participated in the program with Salinas and Seaside. Their projects have included: using recycled materials to build short-term housing for farmworkers on farmland that is temporarily available in Salinas, planning and implementing a pilot farmers market on Echo Avenue in Seaside, and developing business models for cannabis tourism that would create positive spillovers for the local community.

“For the students, the main benefits are to work on business ideas that can create a positive impact in the local community, and to have the opportunity to interact with professionals from the city government and others who care about the region,” Di Gregorio said.

“The projects gave the students a sense of real-world purpose, making them feel like professionals rather than merely students,” Kvitek said. “This was especially evident when they presented their results to the city officials.”

“I learned what it takes to get things done for a community, and how to work with city officials,” said student Robert Banales, who worked on a parks project for Seaside. “Being able to experience city government really left an impact on me and gave me a great set of skills I can use for the rest of my life.”

In the meantime, Fernandez is already thinking about where the program will go next. “We’re flanked by all these cities doing great things,” he said. “Cities have all these aspirations, but they need help from the university to do it.”

Help that CSUMB’s faculty and students are ready and eager to provide.