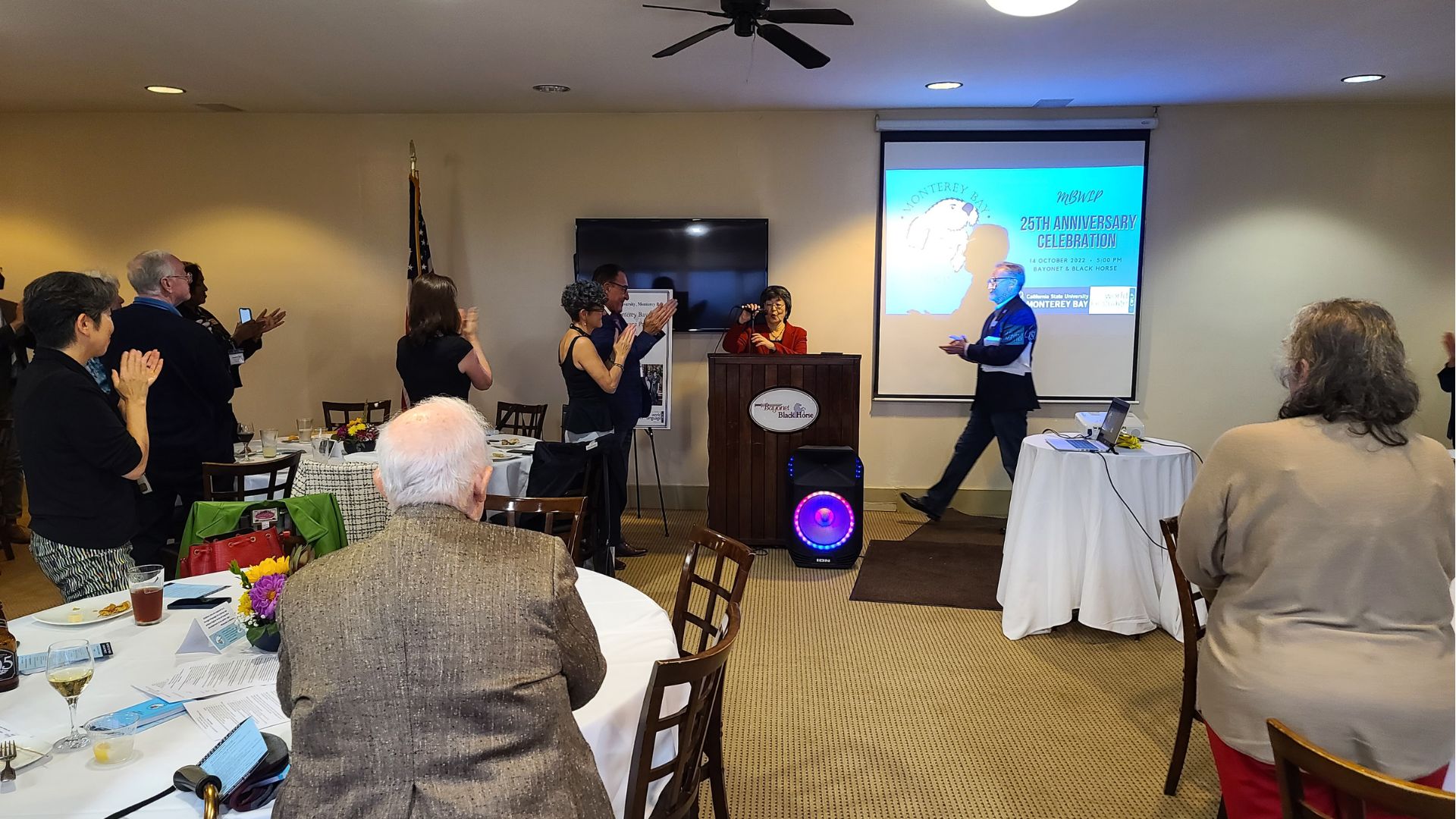

Monterey Bay World Language Project celebrated 25 years

Yoshiko Saito-Abbott at the podium at Bayonet and Blackhorse

November 23, 2022

By Marielle Argueza

On Oct. 14, CSUMB’s Monterey Bay World Language Project (MBWLP) celebrated 25 years at Bayonet and Blackhorse golf club in Seaside. The program promotes and supports educators and students in the learning and teaching of various world languages, with the goal of preparing California students to engage with diverse people and cultures at home and abroad.

It was established in 1996; is housed in the School of World Languages and Cultures in the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences; and is a member of the California World Language Project network.

MBWLP’s program activities, approximately 10 per year, are supported by federal and state grants, are focused mainly on the Monterey, San Benito, and Santa Cruz tri-county area, but also extend to statewide and national conferences. MBWLP team members are K-12 world language teachers who have been recognized as ACTFL National Language Teacher of the Year, CA Teacher of the Year, among other awards and recognition. Since 1996, MBWLP has delivered 280 workshops/seminars and served about 7,000 teachers.

For Yoshiko Saito-Abbott, CSUMB professor of Japanese language and culture, and director for the Language Project, a 25-year milestone may seem like a long time, but time flies.

“The event reviewed a lot of memories over the years. But 25 years goes by really, really quickly,” she said of the anniversary.

The anniversary began with a slide show, and featured remarks from Saito-Abbott and other staff and faculty involved with the Language Project, including Gus Leonard, as well as President Vanya Quiñones, and the dean of CAHSS, Juanita Cole. There were opportunities for current team leaders and newer Language Project participants to mix and mingle. The anniversary was bookended by a game show and a showcase of music and dance performances.

The event also featured remarks from language educators Anne Cappiello, a Language Project leader from Santa Cruz’s Harbor High School, and Dr. Margaret Peterson, executive editor for the Language Project. The latter was an especially dear feature for Saito-Abbott.

Years ago, she was approached by Petersen and others at the University of Texas, Austin. They asked Saito-Abbott, a certified teacher of Japanese, why the university didn’t have a Japanese certification process. The meeting encouraged Saito-Abbott to start the certification process rolling at the University of Texas, Austin. Today, the process still exists, even as Petersen and Saito-Abbott have moved to California for other career pursuits.

For Saito-Abbott the event wasn’t just a momentous occasion to celebrate a quarter of century, a feat for any project, but because they survived the pandemic. The workshops and seminars that they’ve put together have always focused on best practices for teaching one of the most difficult skills to attain in any academic setting.

“Covid was difficult because in language learning, face-to-face is the ideal environment,” she said.

She found that since 2020, teachers across the tri-county area didn’t just find it difficult to adjust from in-person to virtual classrooms, they were also reporting difficulties with hearing students, attendance, and even seeing students’ facial expressions because some students would choose not to turn on their cameras.

During peak pandemic, teachers found that more than ever, they couldn’t turn away from the social-emotional turmoil of their students or their own lives.

“They were seeing students’ struggles with their families, all kinds of things. Getting sick or having their parents get sick. Or having a parent lose a job. Sometimes the teachers were getting sick themselves,” said Saito-Abbott.

Then the effects of such troubled years also had long-term effects: massive learning loss. Not just in language learning but across all subjects.

Rather than being deterred, she says her team leaders and the World Language Project met the challenge. They tailored many of their workshops in recent months away from a laser focus on standard academic attainment and more toward overall wellness and integrating more practices that engage students on a deeper level. In fact, one of their upcoming programs is inspired by such a lesson. Titled “Caring for Self and Others: Promoting Wellness and Connection Through Building Proficiency in a World Language,” is slated for Dec. 5.

Other workshop lessons also focus on student engagement and application on day-to-day life and bigger global problems. Saito-Abbott says they encourage teachers to allow students to research topics like climate change, water scarcity and other global issues and they encourage students to find practical solutions and discuss with their peers.

She hopes that teachers and their students will begin to understand that language attainment isn’t just about communication, but a tool to build bonds, grow leaders, and intensify the impact of their actions as members of an increasingly diverse world.

“Everyone has learned a lot about each other in the pandemic,” she said. “Language isn’t just vocabulary and grammar.”

For more information see the MBWLP webpage.