Seeking Social Justice

July 31, 2020

Professor offers book recommendations, views on Black Lives Matter

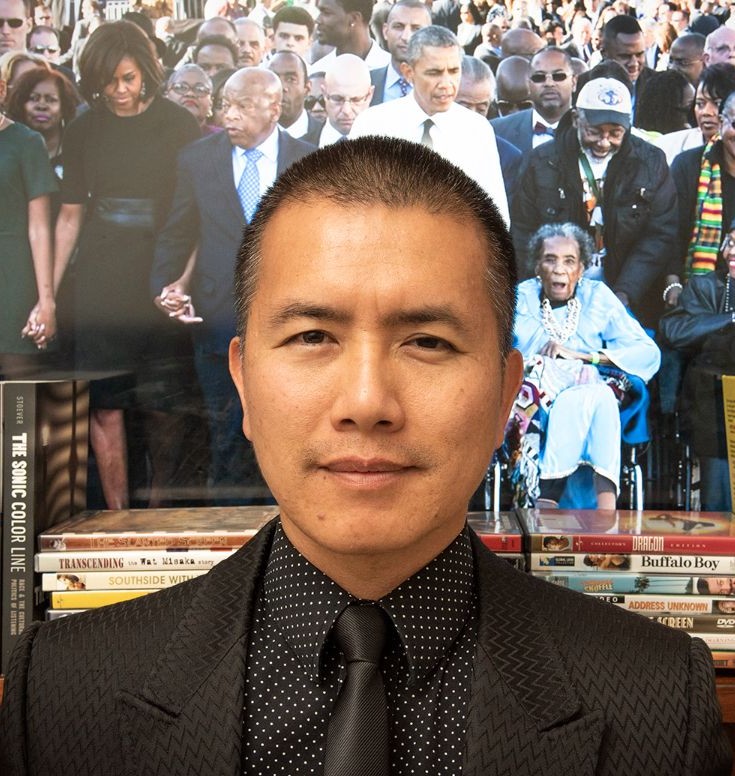

Phuong Nguyen

The third in a series of Q&As with CSUMB faculty about Black Lives Matter and the racial justice movement occurring in our country and around the world.

Phuong Nguyen, an assistant professor in the School of Humanities & Communication, teaches U.S. history and ethnic studies courses including Histories of Democracy, California at the Crossroads, Asian American History, and History According to the Movies. He is the author of “Becoming Refugee American: The Politics of Rescue in Little Saigon,” a history of Vietnamese in Southern California, published by the University of Illinois Press in 2017. Before coming to CSUMB, Nguyen taught at Ithaca College in upstate New York, where he directed the minor in Asian American Studies, co-directed the Ithaca Pan-Asian American Film Festival, and served as a faculty fellow in the Martin Luther King Jr. Scholars Program. He grew up in the Central Coast and attended Monterey public schools from grades K-12.

What does the CSUMB community need to understand about the Black Lives Matter movement?

Three important themes come to mind. First and most important, Black Lives Matter or any other racial justice movement in our country is coming to terms with the systemic nature of racial oppression. What this means is that even if the brutal murder of African Americans is being committed by just a few bad individuals in law enforcement, there isn’t really an effective mechanism in place to hold bad cops accountable for their actions.

Second, identity politics that affirm the humanity and beauty of historically-marginalized groups such as African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans and Latino Americans are fundamentally different from campaigns supporting white pride or white nationalism or Eurocentrism. Racism, whether hate-based or systemic, created a caste system based on skin color by elevating this category called “white” while dehumanizing everyone else, including other white people. Stereotypes were created to justify the harsh treatment inflicted on people of color. It’s thus no surprise that an earlier generation of minorities dealt with racism by whitening themselves — by perming their hair or bleaching their skin or wearing colored contacts or changing their names — in order to fit in.

But later generations stopped apologizing for being people of color. They started emancipating themselves from the colonial mindset of white superiority. If you’re constantly being beaten down, demoralized, dehumanized, and discriminated against, to say that “Black is Beautiful” or that “Black Lives Matter” is identity politics that asserts equality in the face of oppression and prejudice. This is fundamentally different from white identity politics, which are designed to re-inscribe white supremacy or superiority over the rest of society.

.png)

Third, protest is necessary for social justice. Working hard and staying out of trouble is not enough to repeal an unjust system. As Martin Luther King Jr. expressed quite eloquently in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

We must point out the flaws of our system, and demand that society live up to its ideals of “liberty and justice for all,” up to the point of civil disobedience because we have, as MLK stated, “a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” Those protests have taken place in the courts, in capitol buildings, on college campuses, on the pages we read, and in the streets. That’s been the case going at least as far back to the American Revolution.

We are a more just society today because people fought to end monarchal rule and slavery, and fought for universal suffrage, civil rights, marriage equality, cleaner air and water, universal education, better wages, affordable healthcare, and so much more. Hard work still matters, but without protest, what are the odds we are going to be rewarded fairly? Whether that’s on the basis of need, merit, or equally across the board.

Why did you become interested in ethnic studies and social justice?

I think a lot of us in ethnic studies were doing it long before we got our fancy degrees and prestigious formal positions. We grew up here as cultural insiders but as racial outsiders, constantly being bombarded with images suggesting we’re inferior because of the color of our skin, the shape of our eyes, the sound of our name, the language we spoke at home, the texture of our hair, the religion of our ancestors, or the smell of our food.

We knew we had a lot of unlearning to do, but some of us struggled more than others to connect with counter-hegemonic movements in this country. Early on, I found it through books and pop culture. It wasn’t until I took ethnic studies courses at UC San Diego that I was able to connect with people committed to diversity and inclusivity, where I was first exposed to an entire literature on anti-racism and social justice. I met professors who were role models inside and outside of the classroom, where there was nothing wrong with being Asian and American. It was such a meaningful, uplifting experience that I wanted to be part of that tradition for the next generation of college students.

Which books do you recommend to those seeking to learn and understand?

“The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander: This is one of the most important books in the past 10 years because Alexander diagrams with precision the legal history behind mass incarceration and the War on Drugs. She makes the bold argument that these movements are part of a tradition of “white backlash politics” following a period of civil rights reforms.

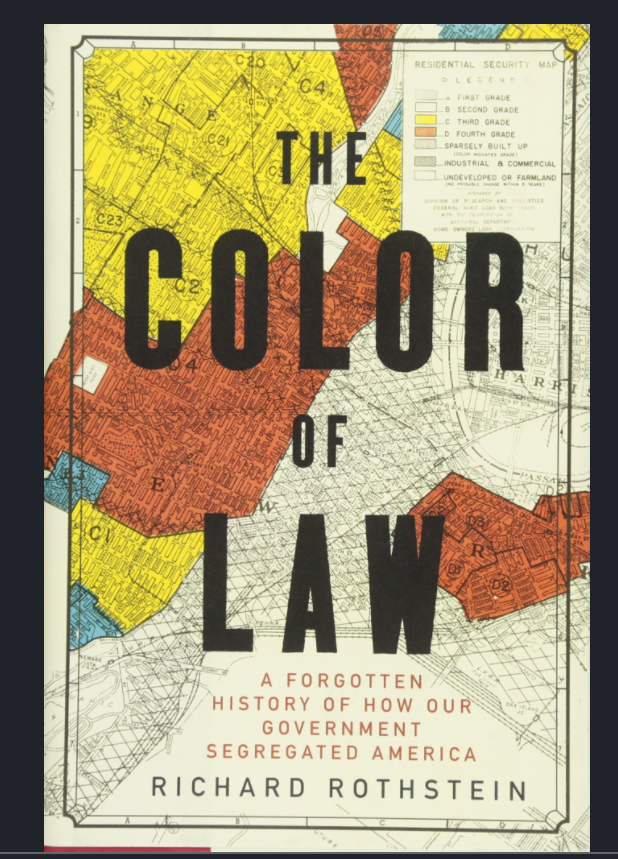

“The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein: This excellent book details the history of government-sanctioned segregation in 20th-century America. With all the mainstream chatter about systemic racism, books like these help us understand clearly what that term means, and how it’s perpetuated by people who are merely following laws and policies. For example, the Federal Housing Administration ban on loans to homes with any sign of Black residents went on for decades until the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. Then there were punitive actions against white people who tried to integrate their neighborhoods.

“Americanah” by Nigerian-born writer Chimamanda Ngoze Adichie: For something more humanistic, I recommend this semi-autobiographical novel following the life of a young professional named Ifemelu, who goes to college in the United States. Though a work of fiction, it’s still one the most entertaining and insightful ethnographies out there because of Ifemelu’s interesting take on how race works in America, and her awareness of how people view her.

How can individuals in the Otter community help ensure inclusive excellence?

Elect leaders who work for social justice and vote for laws that open doors to groups who have been historically denied opportunities in higher education, hiring and contracts because of the color of their skin.

Secondly, we need to heed the words of civil rights activist and writer Audre Lorde when she says, “Without community, there is no liberation.” We need to build community and relationships at every opportunity, so that when we talk about liberty and justice for all, we truly mean it because we know and care about those around us. It won’t solve all of our problems, but it’s a good start.